Spring is an enchanting season almost everywhere, whether its approach is hesitant, primrose by primrose, under a grey northern sky, or it comes overnight in a mad tropical rush of growth. She had left Upton St. Clare beaten upon by chill sleety rain which was battering the early fruit-blossom and stripping the trees of their tender leaves. Here in Touraine spring was reigning triumphant. The warm air had already brought a wealth of gay green to wood and meadow, and covered the gnarled black stems of the grapevines with pale leaf-buds.

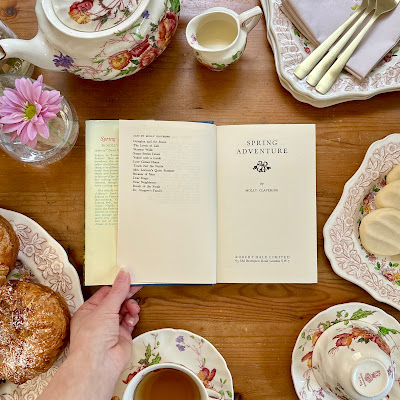

Spring Adventure, Molly Clavering’s fourteenth and final novel was published in 1962 by Robert Hale Limited. She also wrote a non-fiction book, From the Border Hills, and twenty-four pocket novels that were originally published in serial form in The People’s Friend magazine between 1952 and 1976. There is a lot more information about Molly Clavering to be found on Scott’s blog, Furrowed Middlebrow. Dean Street Press have republished eight of her books, including Yoked with a Lamb which I loved. And thank goodness for that, because if it was not for Scott and DSP, I would likely never have found this author that I have come to love. The books that have not been republished are extremely rare. If you are in the UK, I think the National Library of Scotland would be a good resource to look into.

I was over the moon to get my hands on a copy of Spring Adventure, because, as I said it is extremely rare and because I love Molly Clavering’s writing. Since most writers hone their craft over time, I thought this one might even be her best book. Let’s see if this one lived up to my high expectations.

Twenty year old Joanna Clay lives in the tiny—“hardly more than a village”—town of Upton St. Clare. At the outset, Joanna is waiting outside of her house for the post to arrive. When it does, she swipes a letter addressed to her, and goes down a quiet lane to enjoy her letter in private. The letter is from Kenneth, the man she has been seeing, but instead of an affirmation of his love, he is breaking it off with her. She has barely had time to process the letter when she runs into Mr. Trevithick who is out walking his wife’s fox-terriers, Bijou and Toutou. This exchange between Joanna and Mr. Trevithick is pure Molly Clavering. It’s funny and perhaps all the more ridiculous because of the contrast between the well-meaning Mr. Trevithick and Joanna’s very real pain. We also find out she christened him Mr. Terrific, very inappropriately, and we find out that this re-naming of people is something she has done with a number of people throughout her life. This provides us with some insight into Joanna’s character early on. She is not normally crying over men—this is the first time—usually she is loving, light hearted, and looking to have fun.

Back at home, she finds her mother in a state. A letter has arrived from Joanna’s father’s cousin, Nigella Dinwoody. The woman is expected to arrive in time for tea that very afternoon and stay the night.

Miss Nigella Joanna Dinwoody was as imposing as her name. Tall and stately, she towered above Mrs. Clay’s short plumpness in a manner which justified the latter’s complaint that it was like talking to a cathedral to converse with Cousin Nigella. Cathedrals are sometimes breathtakingly beautiful, which Miss Dinwoody was not; sometimes they are majestic, sometimes overpowering, but almost always they are worth looking at, and this Miss Dinwoody certainly was. (15)

Dressed head-to-toe in grey with a “tall and stately” personage, and “long Gothic face”, Joanna describes her cousin as looking like a cathedral. And as odd as it sounds, it was a description that worked for me. I was able to picture Miss Dinwoody better than any other character in this book, including our heroine, Joanna. Whether it is the breakup that left Joanna with more of a devil-may-care attitude, or the blunt honestly of Miss Dinwoody, in this first scene with the two of them we begin to see the strong woman that Joanna is capable of being. She has just turned twenty, but is not employed and still lives at home with a mother who babies her. Miss Dinwoody is planning a research trip to France for the new children’s book she is working on and invites Joanna to come with her as a sort of companion/research assistant. Joanna is shocked, as Miss Dinwoody is a relation that they are not close to and have not visited with much. It seems like Joanna might even turn down the offer.

Then the phone rings. It’s Joanna’s friend Rosamund Wye calling with big news. She’s engaged to none other than Kenneth Quarrinder. The same Kenneth who has just broken up with Joanna by letter. Needless to say, the first thing Joanna does when she extracts herself from that truly nightmarish phone call is to accept Miss Dinwoody's offer to accompany her to France.

As much as this progression makes sense for the plot, my heart fell when I realised this book was going to shift settings. The time Joanna spends out and about in the small town of Upton St. Clare held such promise for colourful characters in a close-knit community where everyone knows everyone else’s business and there are plenty of opportunities for humorous situations. It’s a setting in which Molly Clavering is at her best, and I was a little worried about what taking this show on the road was going to mean for the story.

Clavering does a great job of describing the French countryside, and we see the effect the change in environment makes on Joanna. But there is quite a small cast of characters in the remainder of the book, really just Joanna, Miss Dinwoody, and three young men. Joanna meets the first man, Richard Severn, crossing the channel, and takes an instant dislike to him because he has caught her crying and acts overly familiar with her. The second man, Gervase Deveron who goes by Tim, she literally runs into while looking for the bathroom at the hotel in Tours. Tim is closer to Joanna’s age and she immediately feels at ease with him, treating him like a younger brother. Richard and Tim turn out to be stepbrothers, though they are not traveling together. Richard, who is a Navy Commander, is on a course arranged by his work to improve his French. While Tim has been traveling around France with a friend named Tony, who is our third man. Of course, the brothers both fall for Joanna.

Besides the concierge at the hotel, a shifty character in an antique shop, and some baddies we meet in the last third of the book, that is all we get of local colour in this one. Unfortunately, we don’t find out much about any of these characters outside of Joanna’s observations of them. All of the main characters are British, and if it was not for the fact that the group had to run into some trouble in a foreign country, because all the baddies in this book are French, the group could have just stayed at home. It is not like there is a shortage of castles and stunning landscape that could have been explored in Scotland. But you know, I think I could have overlooked the disappointing use of setting if it was not for the frightful left turn this book takes two thirds of the way through. But more on that later.

Clavering does as beautiful a job of describing the French countryside as I hoped she would. At one point, Joanna goes on a bus trip on her own to Château d’Azay-le-Rideau, outside of Tours, and Clavering lavishly paints the scenes that go wizzing by the bus window. But it is Joanna’s impression of the landscape that I want to share.

And why was this so different from its English counterpart? It was made up of the same component parts: rivers, fields and woodland, farm and village and church, yet one would never for a moment imagine oneself to be in Kent or Hampshire. Perhaps it was that the light was different, lacking the soft brightness induced by a damper climate? Joanna thought this over for a mile or so, but came to no definite conclusion and turned her whole attention to enjoying the passing pageant. (78)

This passage struck me, because I had a similar thought when I was on a train bulleting its way through the French countryside. It may not look so different from home, but you could never mistake one for the other. In classic Clavering fashion, there are beautiful descriptions of the parkland around the château, but what I am particularly interested in is how setting affects her characters.

And yet, nothing she had seen could compare with Azay-le-Rideau. Her preference had not anything to do with sense or reason. She was quite ready to admit that Chenonceau, for instance, was more beautiful, but Chenonceau had made its appeal to her eyes; Azay-le-Rideau, the Lovely Place, appealed to her heart. It might have been partly because it was a happy place; the great events of history, so often tragic, had passed it by. Whatever the cause, she had fallen under its mild and gracious spell immediately she had walked in at the gates, and a part of herself would always belong to it. Could one fall in love with a place? For that was what her feeling for Azay was like, as unreasoning and as irresistible. (84)

It is here that she realises that “Kenneth would not fit into the Lovely Place” as she has christened the Château d’Azay-le-Rideau. As she cannot find fault with the place, then the fault must lie with Kenneth. This is how she realises she does not love him anymore. Joanna is pictured on the dust wrapper gazing at the Château d’Azay-le-Rideau. The château and grounds are open to the pubic, and from the photos on their website, it is no wonder Joanna found this an inspiring place.

I’m sharing the blurb from the first page of this book, which is word for word the same as the blurb found on the inside of the front flap of the dust wrapper minus the first word, which in that case is simply, “Spring”. The blurb basically tells you everything that happens in this book right up to the conclusion, minus specifics.

Springtime, in Touraine, ‘the garden of France’: with blue skies, flowering water meadows, the wide Loire flowing by below the historic châteaux ... everything is so different from her Cotswold home that Joanna, suffering from the shock and humiliation of being jilted in favour of her friend Rosamond, finds her wilting self-confidence gradually restored, though she is determined to have nothing more to do with men.Her elderly cousin Nigella, writer of children's books, who has brought Joanna to France, thinks otherwise but says nothing. Young men ‘bob up’ as Joanna feels, quite unnecessarily, and Cousin Nigella encourages them because she finds them useful. When her interest in history leads Cousin Nigella into strange places, the young men prove very useful indeed; and in the end one of them provides a fitting climax to Joanna's Spring Adventure.

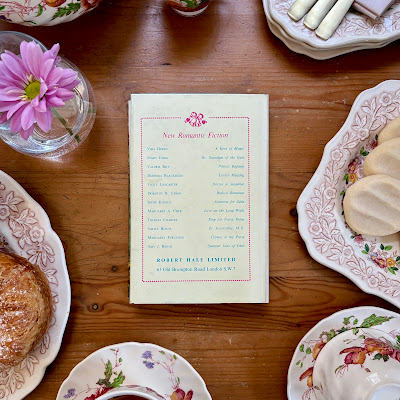

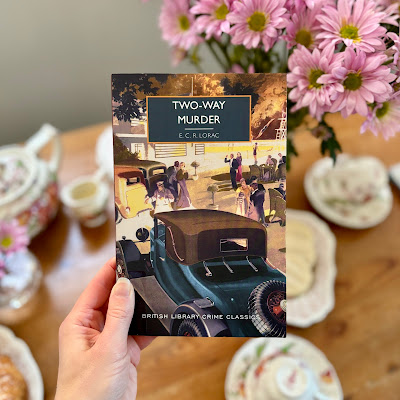

A bit like old movie trailers, which—while enjoyable in their way—make even the best classics sound fairly awful, blurbs on vintage books have a way of making even the best books sound trite. I actually think this blurb does a goodish job of summarising the book. It even hints at something that I didn’t pick up on until after I finished the book and that is the change in tone that I mentioned. The first two thirds of this book are more in the vein of Rosamunde Pilcher’s earlier books than in the Molly Clavering style I am familiar with, that is the writing Clavering was doing between 1936 and 1956. But on page 128 it takes a sharp left turn and becomes a Mary Stewart romantic suspense complete with a kidnapping and a hare-brained scheme the four young adults cook up to go it alone without the help of the police. Then it was an Enid Blyton, with a picnic feast almost immediately after their near death drama. I honestly thought the elderly cousin, Nigella, was not asleep, but dead in the backseat of the car at this point. I was waiting for them to discover the fact in the middle of their scoffing of sandwiches. The final scene was the part that was the most like the conclusion of some of the other Molly Clavering books I have read, which is not terrifically unlike a Rosamunde Pilcher, now that I come to think of it.

This book was not at all what I was expecting. But you know what I was expecting? More of the same Molly Clavering that I was already familiar with, which, let’s be honest is a bit dim of me. Writers are meant to change and grow their craft over time. If you are lucky as a reader you will grow with them, but sometimes your paths diverge and that’s all right too. This book was not a parting of the ways between Molly Clavering and me. I did have a lot of fun reading it. I will admit that is in part due to the novelty of reading a rare title by a beloved author. But it is also because I will always love Molly Clavering. It does not matter how many eligible bachelors and unlikely occurrences she throws in my way, she will always be a writer of breathtaking landscapes, women who love the outdoors, and hilarious situations, to me. As a whole, this book felt a bit all over the place. It did have bits that were wonderful, but I think Molly Clavering filled the hole in the story that was left by not setting this book in a community with a large cast of characters, by tacking on a high stakes adventure at the end.

As this is not a particularly glowing review, and this book is also a hard one to find, I thought I would end by sharing the Molly Clavering novels that I loved and are readily available. Yoked with a Lamb is full of funny moments and clever dialogue. This one also deals with infidelity in a marriage in a way that I think shows Clavering’s ability to write about topics of more depth with skill. Dear Hugo is one I adored. The epistolary novel is not one that always works for me, but it is done so well in this book. This one does not follow an expected trajectory either, with the main character Sara leading a busy and fulfilling life without a romantic partner. I have greatly enjoyed Susan Settles Down and the sequel, Touch Not the Nettle, too. But I suspect you cannot go wrong with any of the Molly Clavering titles Dean Street Press have republished.

***If you got something out of this post, please consider subscribing to my blog. You can find the email sign up on the right hand side at the top of this page (on desktop version only), or click on the link here. You will receive a confirmation email in your inbox (or possibly your junk folder). Once you click to confirm your email address you will receive an email notification whenever a new blog post goes up. And, of course, you can unsubscribe at any time. Whether you subscribe or not, I’m very thankful to you for dropping by.***

This blog post contains affiliate links for Blackwell’s. As a Blackwell’s Affiliate, I may receive a small commission, at no additional cost to you, if you decide to make a purchase through one of the links on my website. I recommend Blackwell’s because I use them myself. This helps support me in sharing—what I hope is—valuable content. Thank you for your support!